“We have been extremely lucky with our singers. Each seemed to join us at the time when what they were doing with songs was just right for the places we were playing. They are virtually a story on their own.”- Duke Ellington

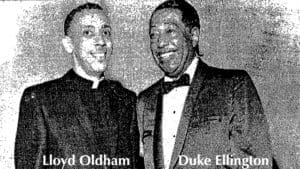

Feisty, precocious, and unaware of the moment’s significance. By his own admission, Lloyd Oldham was all of these things on December 11, 1951. What the then 18-year-old could not fully comprehend was that his rich, booming vocals were about to open the doors for him to a very exclusive club. Inside the Columbia Records studio on 30th Street in New York City that day, Lloyd recorded with jazz icon Duke Ellington. In the process, he joined the ranks of some of jazz history’s biggest names, including Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, and Ivie Anderson, not to mention music legends Frank Sinatra and Rosemary Clooney.

When Lloyd tells his unique story from his private room at St. John’s Home, it quickly becomes clear why his friend and local musician Nate Rawls describes him as “a living legend.” At 83, his dulcet recollections help piece together that story. “I was a singer with the band. Many people were shocked that Duke chose me over all of the singers who auditioned. But I didn’t audition. He came to the house.”

Yes, Lloyd’s path towards joining the world renowned bandleader’s orchestra began at the kitchen table of the Oldham family’s home in St. Louis. Duke Ellington was a friend of Lloyd’s mother Naomi, an elected official in St. Louis. During the 1940’s and 50’s, the Oldham house drew several of jazz music’s top talents for dinner and conversation. “We had this old European-style table that would seat about 20. And that table stayed set most of the time. Especially if there were entertainers coming to town.”

Among other well-known musical acts, Ellington visited the Oldham house a number of times during Lloyd’s formative years. He brought with him a select group of musicians from his Orchestra, including greats like saxophonists Johnny Hodges and Harry Carney, as well as trumpeter Clark Terry. These opportunities to interact with “top of the line entertainers” made a big impression on Lloyd.

Just weeks after impressing Ellington with a solo at the family table, Lloyd came to New York and laid down the vocals for three of Duke’s songs: “Blues at Sundown,” “Azalea,” and “Something to Live For.” Following the recording session, he quickly embarked on Duke Ellington and his Orchestra’s whirlwind tour across the United States.

Lloyd provided lead vocals on a handful of numbers throughout a typical gig. In addition to performing live versions of the three songs he recorded, Lloyd delivered powerful versions of such Ellington standards as “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart,” “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” and ”It Don’t Mean a Thing.” Today, as he reminisces about his time on the road with Duke and his Orchestra, Lloyd breaks into commanding versions of some of the melodies he performed live over six decades ago.

It turns out that Lloyd was not the only Oldham to play with the Orchestra. Earlier in 1951, Lloyd’s sister Norma recorded the song “Love You Madly” and toured briefly with the band. Another of Lloyd’s relatives, his cousin Harold “Shorty” Baker, was a trumpeter who collaborated with Ellington for nearly 20 years, including the time of Lloyd’s stint with the band. “I came from a musical family,” said Lloyd.

As for Lloyd, he performed continuously with Duke Ellington and his Orchestra for many months during 1952. Does that mean that his distinctive baritone harmonies were captured on one of Duke’s two live albums released from early 1952? Lloyd sets the record straight on this one. “Duke would fly two or three top musicians in for the bigger engagements,” explained Lloyd, who would step aside for some of those larger shows in favor of better known singers like Jimmy Grissom and Betty Roche. “But he would keep the rest of his musicians working.”

As for Lloyd, he performed continuously with Duke Ellington and his Orchestra for many months during 1952. Does that mean that his distinctive baritone harmonies were captured on one of Duke’s two live albums released from early 1952? Lloyd sets the record straight on this one. “Duke would fly two or three top musicians in for the bigger engagements,” explained Lloyd, who would step aside for some of those larger shows in favor of better known singers like Jimmy Grissom and Betty Roche. “But he would keep the rest of his musicians working.”

According to Lloyd, Ellington was an extremely kind man, and very respectful of all of the musicians who worked for him, including his singers. “But he was a businessman, and he took care of his business.” An example of this was when one of his vocalists thought that he was becoming bigger than the band itself. “He wasn’t going to have that,” said Lloyd, recalling how Duke took a song from the culpable singer and then called Lloyd to his seat on the bus. Ellington asked “Lloyd, do you know the words to this song?” When Lloyd said he did, Ellington answered “Okay, in the next thirty minutes you’ll be on the floor singing it.”

This ongoing competition among performers kept Lloyd on his toes and supplied him with a growing level of confidence as his time with the Orchestra went on. Whether it was that confidence, the eagerness of a young boy performing with a world class musical act, or another reason entirely, something about Lloyd rubbed Cat Anderson the wrong way. The feeling was indeed mutual, which caused Lloyd and Cat to have several run-ins during his time with the band. “He wasn’t particularly nice to me,” Lloyd says of Cat, a musician known as perhaps the greatest high-note trumpeter of all time. “But he could hit notes like nobody I’ve ever heard,” he diplomatically added.

It was this contentious relationship with Cat Anderson that resulted in Lloyd sharing Ellington’s seat on the bus between cities. After hearing about an altercation between Lloyd and Cat, Naomi Oldham spoke with her friend Duke Ellington about her concern for her young son mixing it up with the much older Anderson, whose relentless orphanage-learned fighting style earned him the nickname of Cat. “Can you separate the two of them?” Norma asked Duke. “Or else I’ll have to bring Lloyd home.” Ellington obliged, and sat Lloyd down next to him for several days.

Although Lloyd recorded just once with Duke, and did not headline top shows at venues like Carnegie Hall and Birdland, his time with Duke Ellington and his Orchestra was notable for another reason. Lloyd became one of the few singers to earn a nickname from Duke—“Bishop,” because of Lloyd’s deep religious faith and evangelical singing style.

The sentiment behind his nickname is one of the reasons why Lloyd the jazz musician never became a household name. “Lloyd was a different kind of singer,” explains Rawls. “He would sing the way he felt.” According to Rawls, Duke would improvise the music to accompany Lloyd’s unorthodox singing style. During the 1950’s, the mixing of genres like jazz and Lloyd’s brand of gospel singing was uncommon. Rawls believes Lloyd was typecast, making it difficult to develop a mainstream following.

Lloyd remembers his departure from the Ellington Orchestra as very amicable. “I just decided I’d had enough,” said Lloyd, citing the grueling travel schedule. “I didn’t want to work that way anymore.” According to Rawls, this was also around this time that Lloyd’s mother became ill, and he was forced to make a choice.

Immediately after Lloyd left the band, he strengthened his connection with his neighborhood church, Union Memorial United Methodist Church. His devotion to the church quickly became a career; one where he could continue using his singing ability and stage presence to touch the hearts of parishioners. He continued to perform with other musicians throughout the 1960’s, and even recorded a rousing gospel soul tune “Richer and Richer.” For years after Lloyd left the Orchestra, Duke also ensured his representatives contacted Lloyd whenever Duke was in town to invite him to guest perform on one or two numbers.

Eventually, Lloyd began splitting his time between St. Louis and Rochester. In the 1970’s, he started a church of his own on Central Park in Rochester. First Church Divine marked its 40thanniversary in November 2015 with an event celebrating Lloyd’s legacy of bringing people together and building a vibrant faith community. Lloyd even started the F.C.D. Hall of Fame to honor those—including former Mayors Robert Duffy, Bill Johnson, and Congresswoman Louise Slaughter—who have made valuable contributions to building social reforms in their community. This Hall of Fame is named in memory of the great Duke Ellington.

Eventually, Lloyd began splitting his time between St. Louis and Rochester. In the 1970’s, he started a church of his own on Central Park in Rochester. First Church Divine marked its 40thanniversary in November 2015 with an event celebrating Lloyd’s legacy of bringing people together and building a vibrant faith community. Lloyd even started the F.C.D. Hall of Fame to honor those—including former Mayors Robert Duffy, Bill Johnson, and Congresswoman Louise Slaughter—who have made valuable contributions to building social reforms in their community. This Hall of Fame is named in memory of the great Duke Ellington.

As for his time with the Orchestra, Lloyd remembers those days fondly. “When I look back at all of my experiences, I think that was the most interesting and cherished one I have.” While a lot has happened since Lloyd dazzled the 20th century’s most prolific musical composer at his family’s kitchen table, it is easy to see and hear how Lloyd made such an impression on the great Duke Ellington so many years ago. Whether he is belting out a song he performed well over a half century ago or complimenting a fellow elder on her outfit, Lloyd’s one-of-a-kind baritone vocals still bring joy to everyone he encounters.

Editors Note: Lloyd Oldham passed away on March 3, 2020 after many years of gracing St. John’s Home with his kind spirit and friendly demeanor.